Treaty of San Stefano

-byTodorBozhinov.png)

The Preliminary Treaty of San Stefano (Turkish: Yeşilköy Anlaşması) was a treaty between Russia and the Ottoman Empire signed at the end of the Russo-Turkish War, 1877–78. It was signed on March 3, 1878 at San Stefano (now Yeşilköy), a village west of Istanbul, by Count Nicholas Pavlovich Ignatiev and Alexander Nelidov on behalf of the Russian Empire and Foreign Minister Safvet Pasha and Ambassador to Germany Sadullah Bey on behalf of the Ottoman Empire.

Although according to the official Russian position, by signing the treaty, Russia had never been intended to anything more than a temporary rough draft, so to enable a final settlement with the other Great Powers[1], this preliminary treaty almost immediately became the central point of the Bulgarian foreign policy, lasting until 1944 and leading to the disastrous Second Balkan War and Bulgaria's even more disastrous participation in World War I.

The treaty provided the creation of a Principality of Bulgaria as autonomous, after almost 500 years of Ottoman domination. March 3, the day the treaty was signed, is celebrated as Liberation Day in Bulgaria. However, the enlarged Bulgaria envisioned by the treaty alarmed neighboring states as well as France and Great Britain. As a result, it was never implemented, being superseded by the Treaty of Berlin following the Congress of the same name.

San Stefano Peak on Rugged Island in the South Shetland Islands, Antarctica is named in commemoration of the Treaty.

Contents |

Effects

On Bulgaria

The treaty set up an autonomous self-governing tributary principality Bulgaria with a Christian government and the right to keep an army. Its territory included the plain between the Danube and the Balkan mountain range (Stara Planina), the region of Sofia, Pirot and Vranje in the Morava valley, Northern Thrace, parts of Eastern Thrace and nearly all of Macedonia (Article 6).

A prince elected by the people, approved by the Sublime Porte and recognized by the Great Powers was to take the helm of the country and a council of noblemen was to draft a Constitution (Article 7). The Ottoman troops were to pull out of Bulgaria, while the Russian military occupation was to continue for two more years (Article 8).

On Serbia, Montenegro and Romania

Under the treaty, Montenegro more than doubled its territory with former Ottoman areas, including Nikšić, Podgorica and Antivari (Article 1), and the Ottoman Empire recognized its independence (Article 2).

Serbia annexed the Moravian cities of Niš and Leskovac and became independent (Article 3).

The Porte recognized the independence of Romania (Article 5).

On Russia and the Ottoman Empire

In exchange for the war reparations, the Porte ceded Armenian and Georgian territories in the Caucasus to Russia, including Ardahan, Artvin, Batum, Kars, Olti, and Beyazit. Additionally, it ceded Northern Dobruja, which Russia handed to Romania in exchange for Southern Bessarabia (Article 19).

The Ottoman Empire promised reforms for Bosnia and Herzegovina (Article 14), Crete, Epirus and Thessaly (Article 15).

The Straits — the Bosporus and the Dardanelles — were declared open to all neutral ships in war and peacetime (Article 24).

Reaction

The Great Powers, especially British Prime Minister Benjamin Disraeli, were unhappy with this extension of Russian power, and Serbia feared the establishment of Greater Bulgaria would harm their interests in the Ottoman heritage. This prompted the Great Powers to obtain a revision of this treaty at the Congress of Berlin through the Treaty of Berlin, 1878.

Romania, which had contributed significantly to the victory in the war, was extremely disappointed by the treaty, and the Romanian public perceived some of its stipulations as Russia breaking the Russo-Romanian pre-war treaties that guaranteed the integrity of Romanian territory.

Austria-Hungary was disappointed with the treaty as she failed to expand her influence in Bosnia-Herzegovinia.

It is interesting to note that the Marquess of Salisbury, the British Foreign Secretary, supported the Russian position and the Treaty of San Stefano. After returning from the Congress of Berlin, Salisbury confessed that in supporting Austria-Hungary instead of Russia, the British had "backed the wrong horse."

According to British historian A. J. P. Taylor: "If the treaty of San Stefano had been maintained, both the Ottoman Empire and Austria-Hungary might have survived to the present day. The British, except for Beaconsfield in his wilder moments, had expected less and were therefore less disappointed. Salisbury wrote at the end of 1878: We shall set up a rickety sort of Turkish rule again south of the Balkans. But it is a mere respite. There is no vitality left in them."[2]

Annex to the Treaty of San Stefano, showing the change of Serbia's borders. |

Annex to the Treaty of San Stefano, showing the change of Montenegro's borders. |

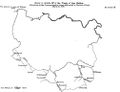

Annex to the Treaty of San Stefano, showing the borders of the new Principality of Bulgaria. |

Annex to the Treaty of San Stefano, showing the change of the border between the Russian and the Ottoman Empire in the Caucasus. |

See also

References

External links

|

|||||